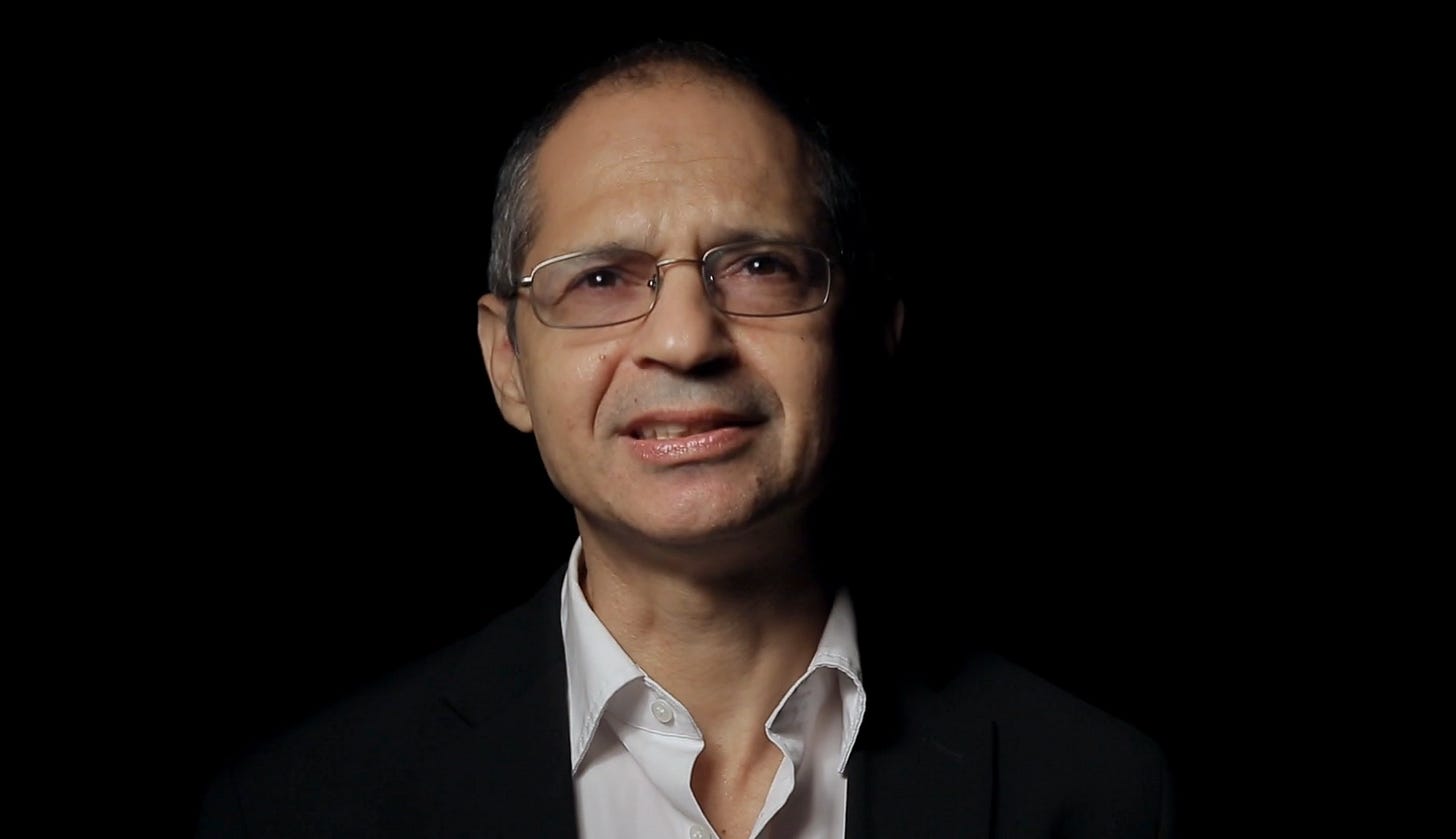

The Interview About the Show About the Class: A Chat with Caveh Zahedi

Chatting with Caveh Zahedi about The Class About the Class and the struggles of teaching and filmmaking.

For the past three decades, Caveh Zahedi has worked on the margins of American independent cinema, making highly idiosyncratic and personal films that generate their power from his personal belief in total honesty. In I Am a Sex Addict, Zahedi details his history with sex addiction through diaristic first person camera addresses and shockingly candid reenactments of his interactions with sex workers.

In similar fashion, Zahedi’s The Sheik and I follows the filmmaker and his family to Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates for a Biennal, where he was commissioned to make a film for the festival with only one rule: Don’t make fun of the Sheik. Unable to work under the constraints given to him, Zahedi runs afoul of the Arts Foundation and faces both legal challenges from Sharjah and an alleged blacklisting from the North American festival circuit by Toronto International Film Festival and DOC NYC programmer Thom Powers.

More recently, Zahedi has developed a fanbase from the TV/web series The Show About The Show. Originally airing on Brooklyn community channel BRIC, The Show began as a clever, self-reflexive experiment that fits with Zahedi’s unique style: each episode would be a reenactment of the making of the previous episode. By the second season, however, The Show becomes a fascinating document of Zahedi’s failing marriage, complete with reenactments of that period, starring himself, his wife, her new boyfriend and his new girlfriend as themselves (at least, until most of them quit and are replaced by different actors).

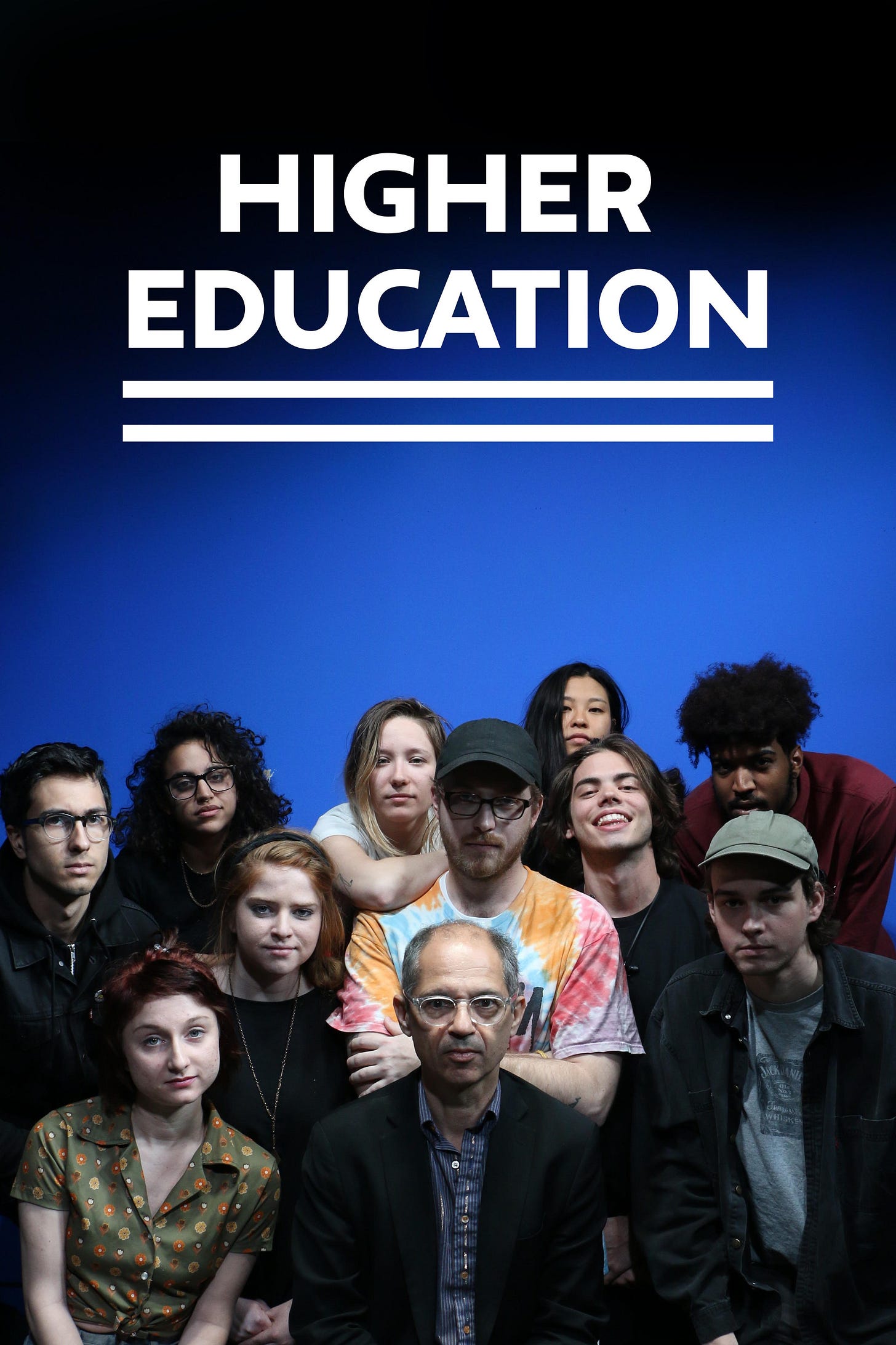

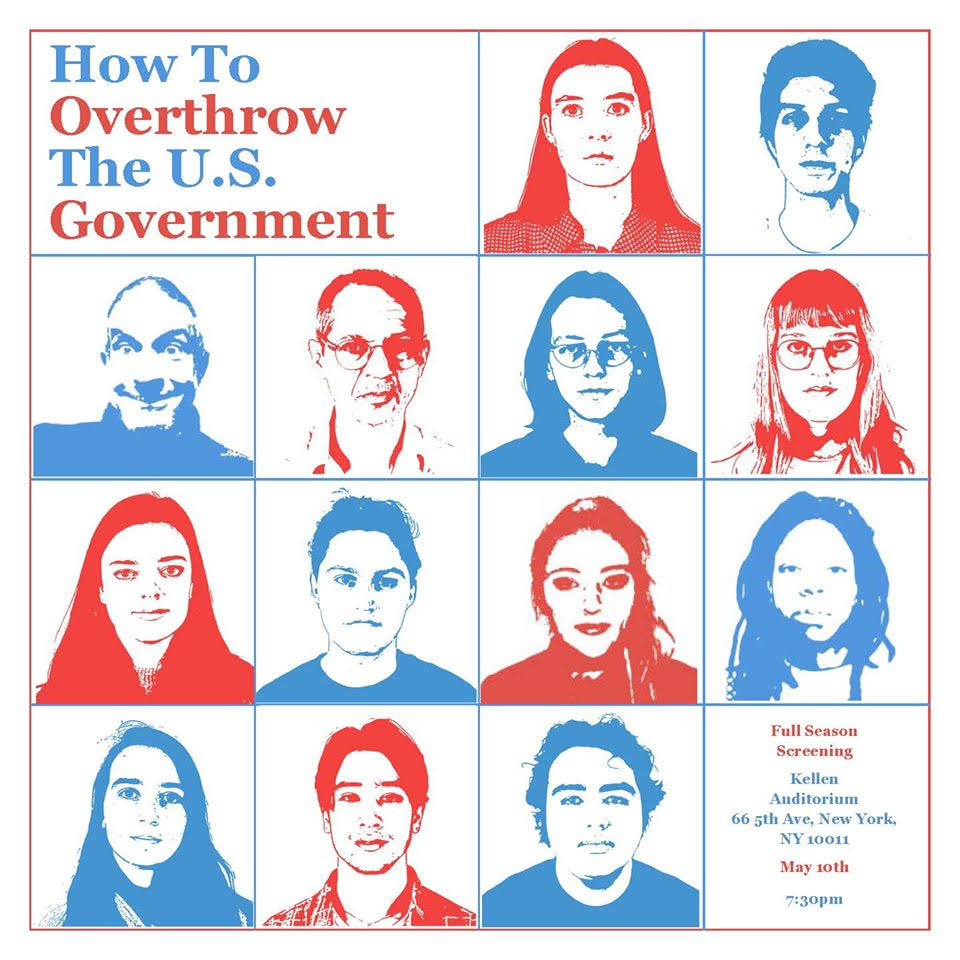

This week, Caveh Zahedi will be in Toronto for a four-part screening of The Class About the Class, presented by Bleeding Edge. On August 27 & 28, Higher Learning 1, 2, & 3 will be screening at Paradise Theatre along with How to Overthrow the US Government (Legally). All four films are the product of a class at the New School in which students, under the tutelage of Zahedi, are tasked with producing a web series about the class. In the process, the students fight with each other, with their teacher and with the school itself. The chaotic atmosphere reaches its peak in the second film after a student accuses Zahedi of treating her differently based on her race and gender, causing a rift in the class. It’s a fascinating series of films, none of which are finished, according to Zahedi, and audiences will get a chance to see his pedagogical methods at work.

We chatted with Zahedi about his films, his philosophy of total honesty and where things stand with the films right now.

Bleeding Edge: How did the idea for this class and the accompanying web series come about?

Caveh Zahedi: I think I got the idea from George Kuchar, who taught a class at San Francisco Art Institute. I knew people who had taken it and they all really liked it, and it sounded fun. I thought it would be fun to teach a class where we're making something together and that it would be more more helpful, really, to participate in an class where you make something that you try to put out into the world. So that was the idea, really, just to make a good production class that seemed relevant. And also, it seemed like web shows are like this thing that anyone can do now without permission and without, you know, gatekeeper kind of stuff. So it seemed like, Let's do this DIY web show and see how it goes. I actually did it a few times before I found a way to do it that worked. I think there were two or three previous iterations that didn't really work.

BE: What was the initial intended viewing format? In the film, you see some clips from screenings that were held at the school itself, but were they supposed to be online in some format?

CZ: Originally I thought we could post them online as we were doing it, and we would get feedback and stuff, but in practice, it was just not possible to do them that quickly. So we would do an end-of-the-semester screening. And, in reality, a semester wasn't enough to pull it off correctly. So we would have a cut and we'd screen it, but then it'd be like, Oh, we still need to do a sound mix, and we still have to tweak things. So that's why they're all works in progress, because I never was able to really finish all of them.

BE: Do the students stay involved as you continue working on them?

CZ: No, they just go off and do their thing. For the first the first year, maybe, a few of the students would come over to my apartment, like once a week and try to keep working on it. And you know, they were finding it and making it better. But then the semester ended, and they all went their separate ways. Everyone eventually just disappears.

BE: Obviously, some of the things that happen in the series or in the films result in some turmoil between you and your students and the school itself. Is that something that you expected when you started to make these?

CZ: No, I didn't, but it became clear very quickly that it causes a lot of problems. I actually stopped doing it because I feel like I was getting in too much trouble, and it was like jeopardizing my situation. So I just said, Okay, it's not worth it. So I stopped, but I really like them, and I think it's kind of a shame, and I'm tempted to redo them now that I've just got renewed for another five years.

BE: How do things stand between you and The New School, not just because of this, but also because of stuff that came up in The Show About The Show about smoking pot with the students?

CZ: I think they see me as a troublemaker, and they're trying to constantly discipline me and make me behave better. So they're constantly giving me a slap on the wrist. Like, I applied for a promotion and they were like, No, we're not promoting you because you're too much trouble. Yeah, they don't like trouble or controversy or anything.

BE: We see part of a contentious Q & A from one of these screenings in the aftermath of the second film, which relates to conflict that occurred in that class. But generally speaking, how do the screenings go? And do the students appreciate what they've created in your class?

CZ: Yeah, I think that that one was special because it was so divisive. But generally, yeah, they love it. And, you know, people enjoy it and are pleased and but then, they have no discipline, these students, they're not good collaborators, for any kind of long-term thing. If you don't get them in that one semester where you're grading them, it's over pretty much.

BE: Do you think that's something specific to The New School and the private university experience, or do you think that would be the case with anybody in that age group?

CZ: I think it's an age and culture thing. I mean, they're not that invested in it. Some people are more than others, and sometimes people will offer to keep working on it after the class. But it's hard to keep doing that, you know, when you're not getting any monetary reward or grade for it. It's such a slow, tedious process, of course, and students don't have that kind of patience. They just don't.

BE: In the second film, the class gets into some sensitive issues concerning race and gender, and you express an attitude about it that might be at odds with the school and with certain students in your class. Do you ever fear that putting this stuff in public will affect your job, or even outside of that, that being labeled a racist or being labeled a misogynist might have more professional consequences? What kind of things do you weigh in your head when you put this stuff out into the world?

CZ: Well, I have it put out into the world because of all this stuff. I mean, these accusations, I find them so ridiculous, and just everything about them is wrong. Like, I'm about as anti-racist as you can be, and as anti-misogynist as you can be. It just feels like it's racist to see race, and all these people who are making such a big deal about race, to me, that seems racist. We're all just people, and we're all the same, it's just stupid. And I know that's not popular, but that's what I think.

There's this thing where you can just call anybody racist or a misogynist and it somehow seems to stick easily. And it doesn't it mean anything. Like, what does that mean? It used to mean something. It used to mean you thought black people were inferior, or you thought women were inferior, but I don't think that! And yet, people are like, No, no, that's what it means anymore. It means nothing. It means that maybe you're not totally on board with a certain kind of hypocrisy that's going on or dishonesty that's happening in the culture. Like, there's some weird emperor has no clothes thing that's happening.

But I've seen a shift happening culturally. Like there was a time a few years ago when you couldn't say those things, and that's when that film really was made. And now I've seen people really reacting against it. like, the whole cancel culture thing is kind of out. And even feminism is kind of, like, out. People are really critical of it now and seeing all the problems with a certain kind of feminism, or a certain way of thinking about that. It's always like a pendulum swing, and it's just going the other direction right now. So I think it's becoming less like that than it used to be.

It's fascistic to reduce everybody to these very simplistic categories and to just condemn them without any kind of description, even, of like, What is it exactly you're accusing this person of? I mean, in that movie, she basically calls me racist and sexist because I don't let her interrupt everyone in the class and call them all racist. Like “That's racist!” No, it's not! That's just a human attempt to be fair to the other people in the class. But people throw that around recklessly. And I think there's been so much of that happening that people are sick of it. The rock is having a lot of ripples. It's complicated, but I don't agree with those accusations.

BE: In a university setting, you have young people who are trying to form their opinions and form their identities, and it almost becomes more dangerous for the teacher to speak out about certain things because of that. But you have this tendency to poke the bear a little bit, in a way that a lot of teachers probably wouldn't. Is there something courageous in doing that, or is that just who you are?

CZ: I think I'm courageous. I mean, I don't think I'm a great filmmaker, but I'm a courageous filmmaker. It takes courage. I think it also takes a certain personality, or a certain set of allergies to hypocrisy, which a lot of people don't have to the same extent that I do. So it's not just courage, it's also some kind of, I don't know, neurosis or something. But, yeah, I think there's been an atmosphere of fear, and there's been a lot of people are acting out of fear. And I just don't believe that people should act out of fear. That's not how you make a better world.

BE: I saw three of them. I haven't watched the third.

CZ: That one was also an attempt to not offend anyone. It's the least controversial. But do you feel like they're problematic?

BE: No, but I would say, watching the second one, in particular, I did have the thought of, What are people going to think about this? Are we going to get in trouble? I'm not proud that I had that thought, but it's definitely there.

CZ: I had it too. I mean, it's incendiary in a lot of ways.

BE: Have you had any contact with that student since the class?

CZ: I haven't. My main worry, really, is she threatened to sue The New School if this film was released. So if I release it and she sues them, they're not going to be happy about that. So I've been keeping it under wraps, but, yeah, I don't know. She has no legal grounds to see them. It's just an empty threat. But people cave to empty threats all the time.

BE: Seeing the chaos that follows your work sometimes, for example with that particular class, or with The Show About the Show, do you ever question your commitment to total honesty?

CZ: I push everything as much as I can without it becoming dangerous. You're always trying to find like, how far can you go before it's dangerous either to your livelihood or, you know, actual danger. It's hard to know sometimes what that limit is, and I think the further you push it, the braver and the more kind of amazing the work is. But if you push it too far, you know it's gonna all collapse on you, and then you aren't making anything anymore.

BE: Do you think that's what happened with The Show? Did you push it just a bit too far?

CZ: I did in the sense that everybody quit and there's no more money, and The Show became impossible to keep going. So I guess I did. Same with The Sheik and I, I pushed that until the whole thing collapsed. But the collapse is part of the film, or a part of The Show. So I think that's still successful. I didn't even know this term when I made The Sheik and I, but people use the term institutional critique to describe certain kind of art, and it basically fits in that tradition, I think. You can criticize an institution until they basically ban you, and then you're outside of it. And that's the art. It's like, here's a piece that got banned, but that's interesting, I think, and worth doing.

BE: You talk a bit about it in the movie itself, but what made you bring Jacques Servin, one of the Yes Men, in as a fellow teacher in the last movie of the cycle, How to Overthrow the US Government (Legally)?

CZ: Well, I felt like I'd gotten in trouble, and I was trying to do something that wouldn't get me in trouble, really. I thought maybe if we co-teach a class, and we focus it not on the classroom dynamics so much as on the external world, it would somehow protect me, and I though that would be fun to teach it with someone else, and I like Jacques. So it was like those three things together. Also we were trying to make a film together, actually, and trying to think of what we could do about the Trump problem, and we were having no luck. And then I thought, Oh, why don't we just teach this class that'll be the film we make. It killed two birds with one stone.

BE: We had KJ Rothweiler up here to screen his movie a few months ago, and he was a former student of yours, but you seem to have collected a sort of community of indie filmmakers who really look up to you. How cognizant are you of that whole DIY, independent scene that's happening in New York, and how involved are you are with it?

CZ: I teach a class where I invite a filmmaker every week to show a film and talk about it. And one of the things I like about that class is I meet all these filmmakers. It's like a community thing. I like that aspect, and I don't have much time to watch things, so I get to watch movies I would want to see, and then I get to hang out with the filmmakers afterwards and get to know them a little bit. So I like doing that. I've met a lot of people through that. And then just from making films, I meet people. I'm not trying very hard to be part of anything. I've noticed some people seem to like my films, but I'm not really an insider. I think I'm an outsider. I don't feel like I'm really part of anything. I just do my thing.

BE: I've been rewatching The Show About The Show recently, and there are some parts where you talk about your relative lack of success as a filmmaker. Is that something that you've come to terms with over the years, or is it something where you appreciate the trade-offs, where you get to teach instead, for example. I'm just wondering sort of what your mindset is on success, and whether you've become a success in your in your own mind.

CZ: I'm of several minds. Part of me is resentful, I wish that I made more money and had more acclaim and could make more of my films. It's frustrating to have a film project you can't make or finish because you don't have enough money. So I definitely am frustrated at my lack of success. At the same time, I think I'm more successful now than I've ever been. So I'm also shifting a little bit, and I'm enjoying that shift, but at the same time, not succeeding has been very growthful. It's really taught me a lot. And being successful has its own traps, obviously.

BE: As a viewer, I think if you had been able to make maybe more conventional films and become successful making more conventional films, then we wouldn't have something like The Show About the Show, which is very unique and something that only you could make.

CZ: I mean, I never wanted to be more successful making more conventional films. I want to be successful making the films that I want to make. That's my only ambition, but I have come to terms with it, and I'm pretty okay with my life. I mean, I wish I had more money. It would make my life easier and I could get more films made. I could hire people, and I could be more prolific. It's really the main thing. There's a film I want to make now that needs some money. I don't have money to make it without funding. But I've pretty much done things on my own terms, which has felt good. And, you know, if I died today, I would die pretty much at peace.

BE: You mentioned that you might do more classes like this, because you got your contract renewed. Do you have any ideas to ensure that it doesn't sort of devolve into chaos?

CZ: You can't control that! I've been teaching these classes recently where we've been doing a play, I'm really into theater right now, and we just did one. It was so good. It was a class on Brecht, and I was like, We're going to do a play at the end of the semester. So I wrote a play in the semester, and we performed it, and, you know, there wasn't enough time to get it right, so it was completely nerve wracking, but it went so well. It was so successful. And it was about the class. We made a play about the class. Basically, it's the film The Class About the Class, but it was a play version of it. I was like, that's a really interesting thing to do, to have people reenact things that happened in the class. I want to do that more, but I want to film these. So I'm trying to get The New School to let me do a thing where I have three classes at once, and one is: we're re-enacting the class, one is: people are filming all the classes, and someone else is editing the footage. So that's kind of a slight variation on this, but that's what I'm thinking I'm going to do next.

BE: Do you have any plans for these four movies going forward? You mentioned that there's obviously a legal threat possibly looming. But do you have any plans to put them out or make them available?

CZ: I really would like to put them out. I'm not sure what the best way to do it is. None of them are quite done, and because of this gray zone around the issues, I haven't put them on the top of the list of priorities, but I think they're really interesting and valuable documents of a time and a place. I'm partly doing the screening because I just wanted to watch them again, I haven't seen them in a long time, and see what they need, and think about how to finish them. And then once I finish them, I guess I'll take the temperature of the culture and maybe put my toes in the water. It's sad, because they're good films, and the one that's most controversial is the best one, I think. And it would be very valuable for society to grapple with this, but it's dangerous to do that for me.